Following the Clues:

Early Knights Templar Regalia

and Certificates

by Aimee E. Newell, Ph.D.

Director of Collections, Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library Lexington, MA

The earliest known record of the conferral of the Knight Templar order in America was at Boston's Lodge of St. Andrew in 1769. It is widely thought that the order was brought to that Lodge by the Irish military Lodges stationed in Boston at the time. The order was conferred under the authority of the Lodge's warrant - not by a separate Encampment or Commandery. By 1780, the Templar order had spread through the colonies. The Boston Encampment, which separated the order from the Blue Lodges and the Royal Arch Chapters in Massachusetts, was established in 1805.

Records of the early order conferrals are sketchy at best. Certificates and regalia from the late 1700s have taught us much of what we know about the early American Knight Templar order, which is that this order and the Royal Arch Degree were often awarded by Blue Lodges. During the late 1700s and early 1800s, Masonic degrees were not standardized as they are today with strict procedures. The early certificates seen here, from Irish and Scottish Lodges, now in the collection of the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts, offer a trail to follow to learn about the early history of the Knights Templar.

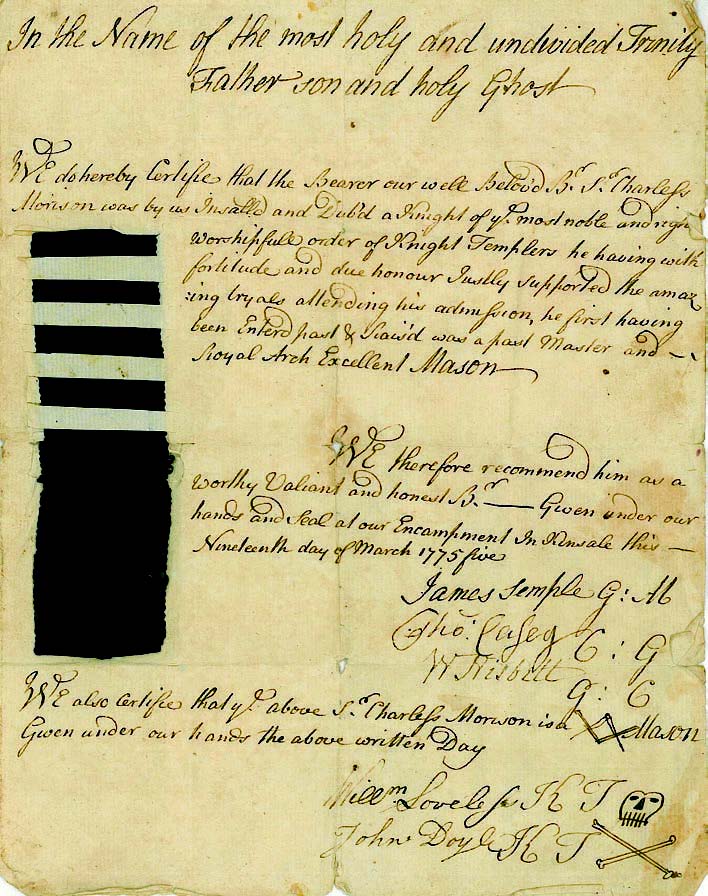

Knights Templar Certificate, 1783, Charles Morison (dates unknown), Staten Island, NY.

Collection of the Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts, GL2004.0002. Photograph by David Bohl.

Charles Morison (ca. 1737-1802) received a Knight Templar certificate in 1783 in Staten Island, New York, under the authority of Lodge No. 212 on the registry of Ireland. It certifies that Morison was "Install'd and Dubb'd a Knight of the most Noble & Right Worshipful Order of Knights Templar" and that he is a "Royal Arch Excellent Mason." An inscription on a stone at Saint George's Church in Saint Catherines, Ontario, provides a few details about Morison's life:

Knights Templar Certificate, 1783, Charles Morison (dates unknown), Staten Island, NY. Collection of the Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts, GL2004.0002. Photograph by David Bohl.

"To the memory of Charles Morison, a native of Scotland, who resided many years at Machilimacinac as a merchant, and since the cession of that post to the United States, as a British subject by election, for loyalty to his sovereign and integrity in his dealings, he was ever remarkable. He died here on his way to Montreal on the sixth day of September, 1802, aged about 65."

One of the earliest mentions of the Knights Templar in Ireland appeared in a Dublin newspaper advertisement for a Saint John's Day dinner in June of 1774. By the mid-1780s, newspaper advertisements in New York show that several Encampments were active in the city, although none mention Staten Island's Lodge No. 212. The Encampment that issued Morison's certificate was held in the British Twenty-Second Regiment of Infantry while the regiment was quartered on Staten Island in 1783, just before it evacuated New York with the rest of the British troops at the end of the Revolutionary War. Moriah Lodge No. 133, chartered by the Grand Lodge of Scotland, also met in this regiment.

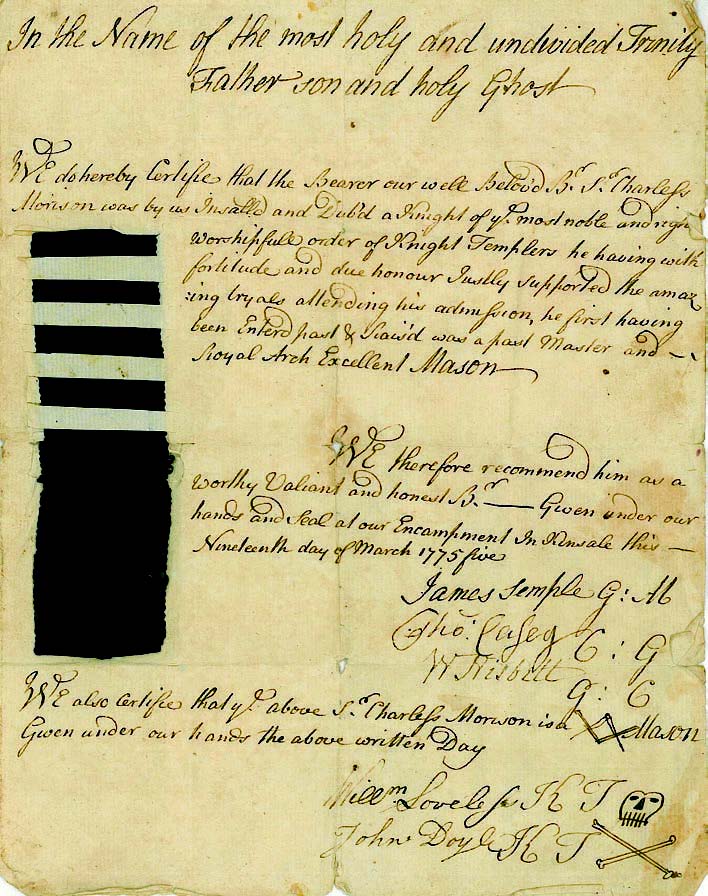

A second certificate for Charles Morison in the collection of the Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts dates to March of 1775. This one, awarded by the "Encampment in Kinsale [Ireland]," certifies that Morison was a Knight Templar, had received the degrees of Past Master and Royal Arch Excellent Mason, and was a Master Mason. This document seems to have been intended, in part, as a traveling certificate. It reads "We therefore recommend him as a worthy valiant and honest Br[other]."

Knight Templar Certificate, 1799, unidentified maker, Maybole, Scotland.

Collection of the Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts, GL2004.10401.

Two additional early certificates in the Grand Lodge of Massachusetts collection show different forms from the ones provided to Charles Morison. Lodge No. 686 on the Grand Registry of Ireland, or St. George's Lodge, "held in His Majesty's 64th or Second Staffordshire Regiment of Foot," had its certificates printed up with spaces to fill in the member's name, date, and signatures. Unfortunately, the member's name on this certificate has faded and is illegible, but it was signed in 1801. Lodge No. 686 formed in 1788 and met until its warrant was cancelled in August 1817.

Knight Templar Certificate, 1801, unidentified maker, Ireland.

Collection of the Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts, GL2004.5795.

In contrast to the printed certificate produced by Lodge No. 686, an "Encampment of Royal Arch Masons in Maybole, [Scotland]" took a simpler approach and had its secretary write out a certificate for Brother James McClellan in March of 1799. "Being a Master Mason from the Royal Arch Lodge Maybole No. 264 of the register of North Britain," the certificate reads, McClellan "was by us exalted to the degree of Excellent and Super Excellent Royal Arch Mason." The certificate goes on to note that McClellan was also admitted as a Knight Templar. Maybole's Lodge No. 264 was established in 1797, but its early history was marked by conflict with another Lodge in town. In 1798, members of the older Lodge complained to the Grand Lodge that No. 264 was guilty of "the most heinous irregularities and carried out their ceremonies in a manner alien to the craft." No action was taken by Grand Lodge until 1800 when a complaint was made again, and the Grand Lodge issued a warning to No. 264. Recently, scholar Mark Coleman Wallace has suggested that the dispute between the two Maybole Lodges may have stemmed from the belief that No. 264 was promoting the aims of the French Revolution and the idea of an Irish Revolution.

Knight Templar apron and sash, 1790-1830, unidentified maker, United States. Collection of

the Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts, GL2004.1114a-b. Photograph by David Bohl.

American Knights Templar wore regalia beginning in at least the late 1790s, but it was governed only by loose traditions until the late 1850s. In 1821, when Jeremy Ladd Cross (1783-1861) published The Templar's Chart, or Hieroglyphic Monitor, he advocated appropriate dress for the Knights. His section on dress suggested "a full suit of black" along with a black velvet sash trimmed with silver lace and decorated with a Maltese cross and a black rosette. The triangular apron was also to be made out of black velvet with silver lace and decorated with a skull and crossbones, a triangle with twelve holes, a cross and a serpent, as well as a seven-pointed star. It is difficult to know how widely his suggestions were followed.

The early apron and sash shown here, from the Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts collection, differ from Cross's recommendations, which may mean that they date a bit earlier than 1821. Their construction materials and style point to an origin in the late 1700s or early 1800s, well before the Knights Templar established standard uniforms. Information about who wore them is unknown. The black-and-white silk apron and black silk sash are hand sewn and hand painted with Masonic symbols. The sash bears an all-seeing eye, Euclid's 47th problem, an arch with a hand holding a sun, steps, a red Saint Andrew's cross, and a red "X" and pound sign. The apron also shows steps, an archway with a sun, and Euclid's 47th Problem, as well as a rooster, and a lamb with a crown and a red flag.

Knights Templar Collar and Jewel, 1842, unidentified maker, probably New York. Collection

of the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library, gift of Samaria Lodge No. 438 and

Monroe Commandery No. 19, 2012.060. Photograph by David Bohl.

Recently, the Scottish Rite Masonic Museum & Library in Lexington, Massachusetts, acquired a Knight Templar collar with a star-shaped jewel from 1842. One side of the jewel is engraved with a triangle, a lamb carrying a flag, and some Hebrew characters. The other side shows a triangle with a circle in the middle. Lettering around the circle spells out the Knight Templar motto, "In Hoc Signo Vinces." In the center is a Christian cross and a serpent. Lettering on this side of the jewel reads "Silas Pratt. Columbian Encampment No. 1 New York, Nov. 4th 1842." According to family history recounted in a letter written by Ruth V. Pratt (1907-1988) in 1938, Silas Pratt (1804-1881) worked as a contractor building the Erie Canal: "built those large locks at Lock Port, N.Y. that Lockport was named after and done it all with Irish and wheelbarrows." Columbian Encampment received a warrant from the Grand Encampment of New York in 1816, but there is evidence that it began meeting in 1810. Unfortunately, its published history for 1842 does not suggest the significance of November 4th, when Pratt presumably received this jewel. It is unclear whether the date had personal significance for Pratt or if it had significance for the Encampment.

Knights Templar Certificate, 1775, unidentified maker, Kinsale, Ireland. Collection of the

Grand Lodge of Masons in Massachusetts, GL2004.0004.

While the documents and regalia described here serve as evidence for us to start to learn more about the beginnings of the Knights Templar in America, they provoke many more questions. I encourage readers who might be interested to seek out new sources of evidence and to help move the history forward.

Sources Consulted:

Sir Elwood Wilbur Goodell, History of Columbian Commandery No. 1 Knights Templar State of New York (New York, NY: E.W. Goodell, 1910).

James T. Gray, Maybole, Carrick's Capital Facts, Fiction & Folks, www.maybole.org/history/books/carrickscapital/freemasony.htm.

Robert Macoy, "Knights Templar: With a Concise History of the Order in the State of New York," Proceedings of the Grand Commandery, Knights Templar, State of New York (New York, NY: Edward O. Jenkins, 1882).

Francis J. Scully, History of the Grand Encampment Knights Templar of the United States of America (Greenfield, IN: William Mitchell Printing Co., 1952).

Mark Coleman Wallace, "Scottish Freemasonry 1725-1810: Progress, Power, and Politics," Ph.D. diss., University of St. Andrews, 2007.

Update: August 19, 2014 Top