A Masonic Secret Weapon: the H. L. Hunley

by Richard F. Muth

Shortly before 9:00 on the night of February 17, 1864, history was made in the waters off Charleston, South Carolina; the first successful submarine attack sunk the U.S.S. Housatonic. It was a feat that would not be repeated for another fifty years. That intrepid submarine was named the H. L. Hunley. A unique weapon, with strong ties to the Confederate Secret Service, the Hunley was designed, financed, built, armed, deployed, and commanded by Masons. With about a dozen brethren directly involved with her, at least two of whom were York Rite Ma-sons, the Hunley may rightly be called a Masonic secret weapon.

The story began in New Orleans during the first year of the civil war. Brother Horace L. Hunley, Secretary of Mt. Moriah Lodge No. 59 and a wealthy attor-ney, was financing and actively assisting marine engineers and Masons, James McClintock of Mobile Lodge No. 40 in Alabama and Baxter Watson in designing and building a submersible boat. Their first design, the Pioneer, was successfully tested in the Mississippi River and Lake Pontchartrain. When the Federal Navy under Captain David Farragut, also a Mason and later the first Admiral in the United States Navy, drew too close, they scuttled the boat in an ultimately futile attempt to prevent it from falling into enemy hands.

Upon relocating to Mobile, Alabama, they joined with the two owners of the Park and Lyons Machine Shop to begin work on their second submersible. After that craft was lost in rough seas, their third and final craft was built, which they called "Fish Boat," later to be christened the H. L. Hunley. During this time, another Mason joined their team when the Army assigned British born mechanical engineer, Lieutenant William Alexander of Mobile Lodge No. 40, to the project. He was a member of the 21st Alabama Volunteer Infantry, which also provided them with the assistance of another of its young Lieutenants who was back in Mobile recovering from a recent wound to his leg.

Lieutenant George E. Dixon, a former steam ship engineer, had a somewhat remarkable tale to tell. Before leaving for battle, his sweetheart, Queenie Bennett, had presented him a good luck token; a shiny twenty dollar gold piece. During the battle of Shiloh, he was struck by a minie ball that hit the cherished coin in his pocket, thus averting a more serious and possibly mortal leg wound. Dixon had the heavily bent but decidedly lucky charm inscribed and kept it with him always. He also carried a gold pocket watch with a Royal Arch fob on the chain. Dixon was raised on May 4, 1863, in Mobile Lodge No. 40 where McClintock and Alexander were members.

Building these iron boats required considerable financing which Horace Hunley could no longer provide as he had up to this point. In looking for more backers, they soon found two fellow Masons from Lavaca Lodge No. 36 in Texas; Dr. John R. Fretwell, who would be Grand Master of Texas in 1868; and Edgar Singer, a relative of the famous sewing machine maker. Singer held the rank of army Captain as the leader of the "Singer Secret Service Corps." They were in town to install the torpedoes (what we now call mines) they had invented in Mobile Bay, devices which would later prompt Brother Farragut to issue his famous order, "Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead." Hunley was also interested in the "Fretwell-Singer torpedo" as a possible armament for the submarine. Hunley and Singer each provided the substantial sum of five thousand dollars toward the building of the third submarine, with an additional five thousand dollars coming from three other inves-tors, for a total of fifteen thousand dollars (nearly three hundred thousand dollars today). Those other investors were all members of Singer's group and of his Masonic Lodge; John Breaman, Robert Dunn, and "Gus" Whitney, a relative of the cotton gin inventor.

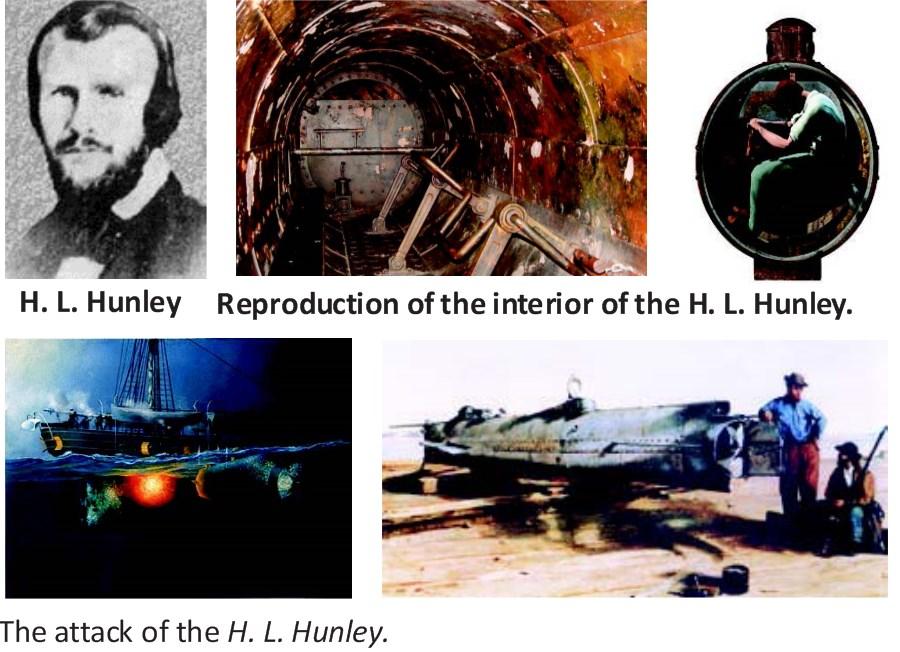

McClintock improved upon his pre-vious designs for that of the third boat. Although still human powered, it was bigger and had several technological advances. She was sleek and hydrodynamic with flush rivets. She was forty feet long with an interior about four feet high and three and a half feet wide. Seven men would sit along the port side and turn an offset hand crank that utilized reduction gears and a large flywheel to increase propulsion while the commander operated levers to move the rudder and dive planes. There were two pumps with multiple valves to fill and empty the ballast tanks as well as drain the bilge and a bellows to bring in fresh air via two snorkel pipes. Two watertight hatches on short towers allowed for crew access through openings of about twenty-one by six-teen and one half inches. The forward one also let the commander see out via four small view ports. Twelve glass "dead lights" lined the ceiling to allow some light to enter the white painted interior when the boat was on the surface.

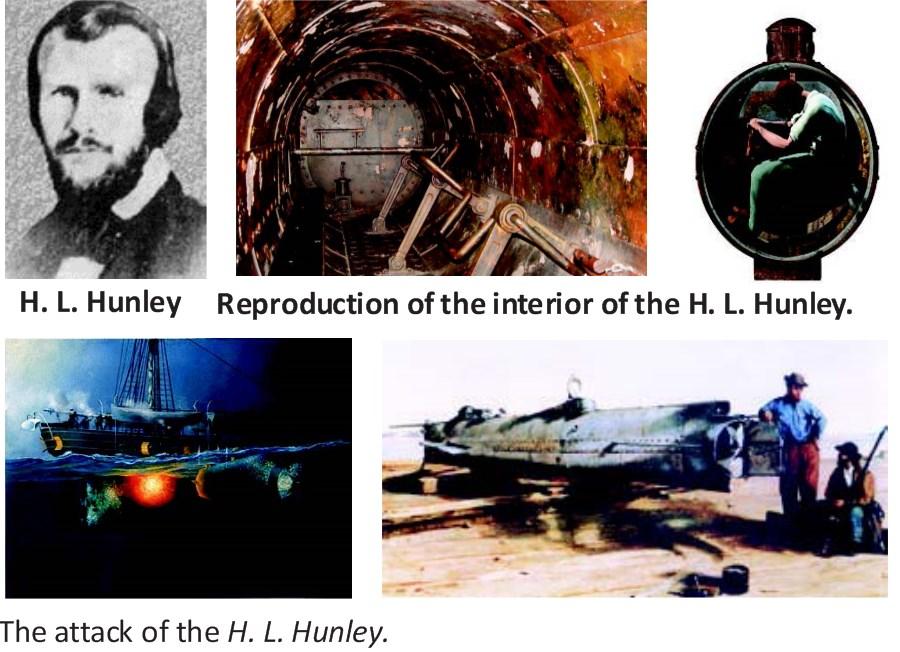

After several test cruises, on July 31, 1863, during a demonstration in Mobile Bay, the Fish Boat successfully dived under a target coal barge and sunk it with a floating torpedo she had towed behind. After resurfacing, she returned to port, having impressed several Confederate officers who witnessed the event. None-the-less, they were not confident that Mobile was where it should be deployed, and instead, recommended its use to the commander at the blockaded port of Charleston, South Carolina. There, Watson and Whitney met with their Masonic brother and Sir Knight, Lieutenant General P. G. T. Beauregard, who wired a request that the boat be sent to him "as soon as possible."

During the initial trials in Charleston harbor, a series of accidents and errors caused the unforgiving boat to sink twice, but she was recovered each time. Tragically, these mishaps took the lives of thirteen members of the two crews, including the man for whom she would then be named, Brother Horace L. Hunley. General Beauregard was appalled by what he saw when the bodies were recovered, and pro-phetically declared the boat to be "more dangerous to those who use it than to the enemy," but Brother Dixon still believed in her, and the young Lieutenant convinced the General to allow him to form another crew and try again. They also decided that a towed bomb was too problematic, and arranged for her to be armed instead with a "Singer torpedo" on the end of a sixteen foot iron spar attached beneath her bow.

On that cold February night, Dixon and seven volunteers set out into the harbor toward their target in the Union blockade nearly five miles away. At about 8:45 p.m., Federal sailors onboard the U.S.S. Housatonic, cautioned by orders from Rear Admiral and Mason John Dahlgren regarding rumors of submersible attack boats, spotted something decidedly suspicious in the water close amidship. They opened fire on it with small arms but to no avail. Moments later, an explosion ripped open her hull at the stern, and in roughly five minutes the Housatonic had sunk, killing five men. Sometime later, a "blue light" was spotted on the water. This being a prearranged signal for a successful mission, bonfires were lit by Confederate troops on shore to guide the Hunley home, but she did not return and was later presumed lost someplace in the harbor.

Her exact location was uncertain until 1995, when a project lead by bestselling author Clive Cussler positively identified her. She lay about a hundred yards past where the Housatonic went down, hidden under several feet of protective silt. Five years later, on August 8, 2000, the Hunley was recovered from the bottom of Charleston harbor, and after one hundred thirty-six years, she finally returned home. Excavation of her silt filled interior lead to the recovery of the crew's bodies. During that painstaking process, next to the skeletal remains in the front of the craft, surrounded by the remnants of a uniform, were found a gold watch with Royal Arch fob and a heavily bent gold coin with an inscription bearing the initials G. E. D.

General Beauregard's last order regarding the Hunley was to "pay a proper tribute to the gallantry and patriotism of its crew and officers." On April 17, 2004, delayed by one hundred forty years, that order was carried out as the remains of the Hunley's final eight crewmen were laid to rest with full military honors. They were buried in Magnolia Cemetery, next to the thirteen men lost from her previous crews. Civil War re-enactors from units representing several states were on hand to pay their respects and escort the bodies in a solemn four-mile procession. Marching with them were approximately fifty men in Masonic regalia, including the full Grand lines of both Alabama and South Carolina. With hundreds of brethren in attendance and witnessed by both the public and the press, Brother Dixon also received a Masonic funeral service. Us-ing the ritual published by the Baltimore Masonic Convention of 1843, it was performed by a Past Master of his own Mobile (now called McCormick-Mobile) Lodge No. 40, Worshipful Brother Wayne E. Sirmon, an officer of the Grand Lodge of Alabama.

Many of the details of this fascinating tale remain lost to us, and some of what we think we know continues to change as new information is literally uncovered. The H.L. Hunley is slowly revealing her mysteries as scientists work to complete her conservation. For many, the Hunley is but a little known oddity of the Civil War, and too few are aware of this history making event. Even to many who do know her story, the Hunley's Masonic connections remain hidden, but to those who have been enlightened, she was not only a remarkable and innovative craft, she was also truly the Confederacy's masonic secret weapon.

You may see many recovered artifacts, including Brother Dixon's watch and coin, at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, in North Charleston, South Carolina. Tours of the Hunley restoration are given on weekends by the "Friends of the Hunley." The author found it to be a moving experience. Visit www.hunley.org for in North Charleston, South Carolina. Tours of the Hunley restoration are given on weekends by the "Friends of the Hunley." The author found it to be a moving experience. Visit www.hunley.org for more information.

Some of the works consulted include:

"Confederate Submarine H. L. Hunley" by Herbert S. Goldberg, 33°, Scottish Rite SJ Internet Articles, Nov.-Dec. 2004

The H. L. Hunley: The Secret Hope of the Confederacy, by Tom Chaffin, Macmillan, 2010

"Mr. Hunley's Mobile-built 'Fish Boat' Makes History,"Alabama Seaport (State Port Authority magazine), February 2012

Raising the Hunley by Brian Hicks and Schuyler Kropf, Ballentine Books, 2002

"Singer's Secret Service Corps: Causing Chaos During the Civil War," by Mark K. Ragan, Civil War Times magazine, Nov/Dec 2007

Sir Knight Richard F. Muth is Commander of Beaver Valley Commandery No. 84 in Beaver, Pennsylvania, and can be contacted at Richard.Muth@comcast.net.

Knight Templar Magazine

ARCHIVE of SELECTED ARTICLES by TITLE