- Editor's Note: The dictionary defines Edicule or Aedicule as a small construction or a shrine, designed in the form of a building.

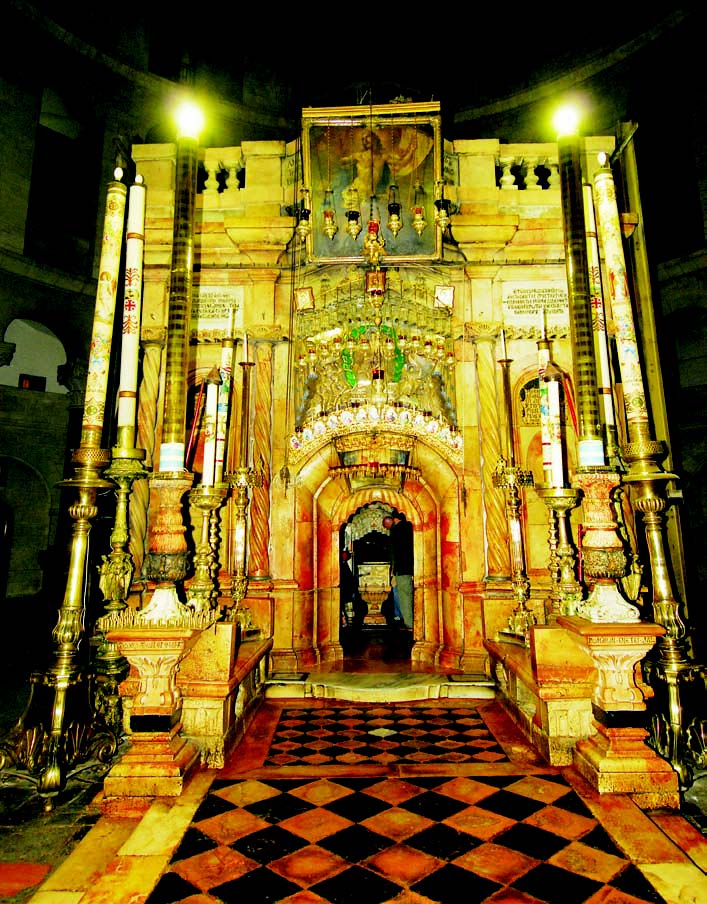

The present structure - the building that houses the Tomb - is not old; it was constructed in 1809-10. The building is called the edicule, which means a little house. It is the size of a very small chapel and stands to the west within a larger building that encompasses it, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

The book from which I am taking this information is titled The Tomb of Christ and was written by an expert in that field, one Martin Biddle, in 1999. It is a detailed examination of the tomb and edicule and their history based on archaeological findings. This history should not be confused with the history and archaeology of the larger building in which it is contained, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

Comprehensive information on the history and archaeology of the tomb itself is not easy to obtain, and so I make no apologies for using this one reference as the primary source of information for this presentation. I will be frequently quoting and summarizing the author's work as it is very clear and succinct.

The Tomb and Edicule

And now to the tomb and edicule. The following quote sets the scene:

"Jesus was executed outside Jerusalem in 30 or perhaps 33 AD. Ten years later, the places of his crucifixion and burial were incorporated within the walls by the expansion of the city. Decades later, these places were buried beneath immense dumps of rubble brought in by the Romans to level the area. Even so, Golgotha, the place of crucifixion, was still pointed out inside the city three centuries later. It served as a landmark for excavations which discovered several rock-cut tombs under the rubble. For reasons never stated, one of these tombs was immediately hailed as the tomb of Christ. The emperor Constantine ordered that Golgotha and the tomb should be preserved and embellished and that a great church should be erected beside them. This basilica, known as the Martyrion, The Testimony, or The Witness was dedicated on September 17, 335, inside the walls of the Roman veteran colony of Aelia Capitoline, soon again to be known by the ancient name of Jerusalem."

There are two streams of thought and reflection in the writings that are consulted for eyewitness accounts of the tomb and its environs. They are the structural and the devotional. This is not at all surprising. We have similar streams running through the Gospel narratives, such as the historical and the spiritual. I am focusing on the structural history of the tomb and edicule that covers it. Of course, the history and archaeology of the larger building encompassing it, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, is most important as it gives us various markers in history of the site and structures such as the damage and destruction of both of them during the centuries.

- From the Beginnings to its Destruction in 1009

The structural sequence of the tomb is conventionally divided into six distinct periods:

1. The construction and "use" of the original rock-cut tomb until buried under the fill of Hadrian's works in 135.

2. The tomb buried under Hadrian's works from 135 until uncovered ca. 325.

3. The edicule created by Constantine around the tomb until its virtual destruction by the Caliph, al-Hakim, in 1009.

4. The edicule as rebuilt in the early eleventh century, embellished by the Crusaders, and later stripped and in decay with only minimal repair until its rebuilding in 1555.

5. The edicule as rebuilt "from the first foundations" by Boniface of Ragusa in 1555 until it was damaged by fire in 1808.

6. The edicule as rebuilt by the Greek architect Komnenos in 1809-10 which survives today.

Visual Sources - 4th Century to 1009

What visual evidence do we have of the tomb of Christ? Well, during the Constantine period and later, the tomb appears in a wide range of media, painting on wood and vellum, ivory carving, stone sculpture, mosaic, metal, pottery, and glass.

As archaeological evidence is not possible to obtain in the present structure, we have to rely on visual evidence in drawings, paintings, and carvings for some idea as to what the tomb and edicule looked like in those early years. These depictions of the tomb and edicule can be placed in the following four categories:

1. A rock-cut tomb in a rock face

2. An empty sarcophagus with the risen Christ above

3. An elaborately architectural tomb structure, usually of two stories

4. A single-storied structure with a conical roof and lattice grilles

The first two are non-representational and are really devotional etc. Even the last two are debated, and many believe that they do not reflect the written descriptions of the Constantine edicule. So, it would appear that it is not possible to establish exactly what the original tomb looked like!

There are also life-size copies of the edicule in several countries e.g. Bavaria of the 12th century. What adds to the confusion and complexity of this investigation is that the edicule saw several changes during the medieval period. It was totally destroyed in 1009, and there were major rebuildings in 1555 and 1809-10 (which is basically what we see today). In the 11th century, a cupola was added to the edicule, and we see today the edicule with a rebuilt cupola.

One of the representations of the edicule and chamber in the Middle Ages is crusader coins. These present a stylized representation of the edicule, or precisely, the tomb chamber. They were probably struck during the siege of Jerusalem in 1187 from metal taken from the cladding of the edicule.

The Edicule Between the 4th & 11th Century

Eusebius' account of the discovery of the tomb in the course of excavations undertaken following the Council of Nicaea in 325 and his description of Constantine's church, the Martyrion, with its associated structures have been the subject of many detailed discussions over the last century and a half. In recent years, discussion has focused on the curious fact of Eusebius' apparent failure to mention Golgotha or the finding of the true cross and upon the contrasts between his writings and those of Cyril. These studies have gone far to clarify the silences, hidden meanings, and changes in focus of Eusebius' words as he distilled his thought in the Theophany shortly after 324 and addressed in turn the congregation at the dedication of the Holy Sepulcher on September 17, 335, the emperor on his thirtieth jubilee in Constantinople on July 25, 336, and posterity.

325 AD

Makarios, bishop of Jerusalem, received permission from the Emperor to destroy the temple of Venus in order to locate the tomb of Christ. The fill covering the site was removed, and indeed the tomb was found. But what was found?

Apparently there was originally a hollowed-out rock, a covering in front of the entrance to the sepulcher, but this had been cut away. This hollowed-out place in front of the tomb was presumably an open and unroofed or partly unroofed forecourt or antechamber cut in the rock face. This was a feature of Jewish tombs of the period and an excellent example of this is the so-called "Garden Tomb" situated outside the city walls of today.

This whole area was developed by Constantine into the edicule we now recognize.

Cyril claimed that the stone that had closed the tomb was still there! Eusebius hailed the discovery as "the august and all-holy monument ('testimony' or 'proof') of our Savior's Resurrection."

I will pass over the debates that have raged down the centuries as to whether or not the tomb so discovered is that belonging to Joseph of Arimathea and in which our Lord was laid.

The Edicule from 1009-10 to the Present Day

The rebuilt edicule of 1566 vanished in the rebuilding of 1809-10. With the advent of the printing press, there are many woodcuts of the edifice as well as the usual carvings that show us what it looked like during this period. Also, full scale models were built and set up in Europe as places of devotion.

Some of the interesting objects made in the form of the edicule are silver artophoria - containers for the Holy Bread.

The edicule survives today, and the 19th century visual sources (drawings and early photos of the 1830s) provide us with useful information. In particular they show the number of ornaments (lamps, candles, and candlesticks, frescoes etc.) that adorned both the outside and inside of the edicule.

As some of the painted decorations are now completely covered in smoke stains, these 19th century representations are very informative.

The rain also got through the Church of the Holy Sepulcher roof onto the edicule in the early 19th century. Thus the edicule has been ravaged by time, the elements, and the destructiveness of man.

- The Tomb of Christ in the Gospels and Later

Having surveyed very briefly the history of the tomb and edicule, I would like to go back again to the beginning of this story and reflect on the information contained in the Gospel accounts.

In regard to the original tomb in which Joseph of Arimathea laid the body of Jesus on the evening of the day of crucifixion in 30 (or less likely 33), we have the direct evidence only of the Gospels. It is probable that none of the writers witnessed the events of that day and no surprise therefore that the accounts they provide are not entirely consistent. The texts of the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) describe the crucifixion and burial in broadly similar terms, but John is more detailed, not least about the tomb itself.

The accounts are quite short: Matthew 43 verses (27:32 to 28:8), Mark 36 verses (15:20 to 16:8), Luke 41 verses (23:26 to 24:10, and 24:22-4), and John 44 verses (19:17 to 20:18). The evidence they provide for the location and nature of the tomb may be summarized as follows.

Jesus was taken out [i.e. of the gate of the city, cf. Hebrews 13:12,13] to a place called Golgotha, which means the place of a skull, where they crucified him. Multitudes stood by watching or passed by and derided him, and many read the title over his head, "for the place ... was near the city." A rich member of the council, Joseph of Arimathea, took away his body. In the place where he was crucified there was a garden and in the garden a tomb, a new tomb where no one had ever been laid. In this, Joseph's own new tomb which he had hewn out of rock, they laid Jesus, and Joseph rolled a stone to or against the door of the tomb.

[The next morning] the women, the two Marys and Salome, went to the tomb. They found the stone rolled away. It was very large. An angel [had] rolled back the stone and sat upon it. Peter and another disciple came out (i.e. of the city) and went toward the tomb. Reaching the tomb first, the other disciple stooped to look in. Peter and the disciple went into the tomb and then went back to their homes (i.e. into the city).

Mary stood outside and stooped to look into the tomb and saw two angels sitting where the body of Jesus had lain, one at the head and one at the foot. The (three) women entered the tomb and saw a young man sitting on the right side, or two men stood by them. The women went out and departed and returning from the tomb told this to the apostles.

Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem. Photo copyrighted by Pavel Bernshtam.

- The essential "facts" seem to be these.

(i) The tomb was outside the city in a cultivated area or garden and was in the place, i.e. presumably not far from the place, of crucifixion.

(ii) It was the tomb of a rich man, previously unused, new-cut in the rock, and closed by a large stone which could be rolled to or against or across the door.

(iii) To look into the tomb, it was necessary to stoop.

These few "facts" are about as much as can be extracted from the Gospel accounts. They can only be interpreted in the light of existing knowledge of contemporary Jewish burial practice in the Jerusalem area, and for logical reasons, must not be explained in terms of the possible form of the tomb inside the present edicule. What is clear is that the kind of tomb suggested by the Gospel accounts is consistent with what is now known of contemporary practice in the Jerusalem area: i.e. a rock-cut tomb, a low entrance closed by a moveable stone, and a raised burial couch within. The difficulty is perhaps that such a tomb is too simple: burial couches on more than one side, long narrow rectangular niches or loculi (kokhim) in which a body might be inserted at right-angles to the walls of the tomb, and multiple chambers are commonplace. The absence of such features may be due to the sparseness of the Gospel accounts. They may not be mentioned because they were thought to be irrelevant, but that does not mean they were not there. In a new tomb, however, they are not perhaps to be expected. It was only with time that additions were needed, and the more complex Jerusalem tombs are clearly the product of successive generations.

The traditional interpretation of the tomb as having a single arcosolium on the right-hand side and a rolling stone smoothly dressed and of almost mechanical perfection is heavily influenced by the supposed form of the tomb discovered in 325/6 and now located beneath the rotunda. If we limit ourselves strictly to what can be derived from the Gospel accounts, a wider range of possibilities emerges with a correspondingly wider range of parallels readily available in the contemporary rock-cut tombs of the Jerusalem area.

Although there has been no lack of surmise, nothing whatever is known of the later history of the tomb of the Gospels in the period down to 135. Adjacent tombs were presumably emptied when the occupied area of the city was extended northwards ca. 4 AD. Whether or how this expansion or the wars and sieges of 66-70 and 132-135 affected the tomb is quite unknown.

The foundation of Colonic Aelia Capitolina by Hadrian ca. 130 on the ruins of the city destroyed in 70 brought major changes to the area. But here we have a logical difficulty. The evidence for Hadrian's works relates to the tomb discovered ca. 325, the tomb which lies today beneath the rotunda of the Holy Sepulcher. The view that this tomb is the same as that described in the Gospels depends upon Eusebius' assumption that they were one and the same. Everything learned about the site by modern investigation shows that this could be the case, but there is no proof. In describing here the effect of Hadrian's works upon the site, it has to be clear that we are talking of their effect on the site of the tomb now located beneath the rotunda and not necessarily therefore upon the tomb described in the Gospels.

According to Eusebius' Life of Constantine, the whole site had been covered with a great quantity of earth and paved with stone, and on this a temple to Aphrodite had been erected over the "sacred cave," i.e. the tomb. Jerome adds the information that this situation had lasted about 180 years, from the time of Hadrian to the reign of Constantine (actually about 190 years) but asserts that it was a statue of Jupiter which had stood over the place of resurrection (i.e. the tomb) and a statue of Venus on the rock of the cross. By the time Jerome wrote this letter ca. 395, knowledge of the previous situation seems already to have become confused. This confusion may be due to Eusebius who wrote his Life of Constantine, in which the temple is attributed to Aphrodite ca. 337, more than a decade after its demolition.

The Gospels imply that the crucifixion and burial of Jesus took place outside the city walls. When Bishop Makarios of Jerusalem sought the burial place ca. 325, he excavated a site within the walled city and located a tomb that he and others accepted as the burial place of Christ, and which has ever since been the focal point of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in its successive forms. We now know that there is no real conflict in the two accounts. Although no part of the second wall has yet been identified with certainty, all scholars seem agreed that Kenyon's Site C and Lux's excavations under the Redeemer Church provide good evidence that the area of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was outside the city until the construction of the third wall by Herod Agrippa in AD 41-4. The traditional sites of the crucifixion and burial have remained within the city ever since.

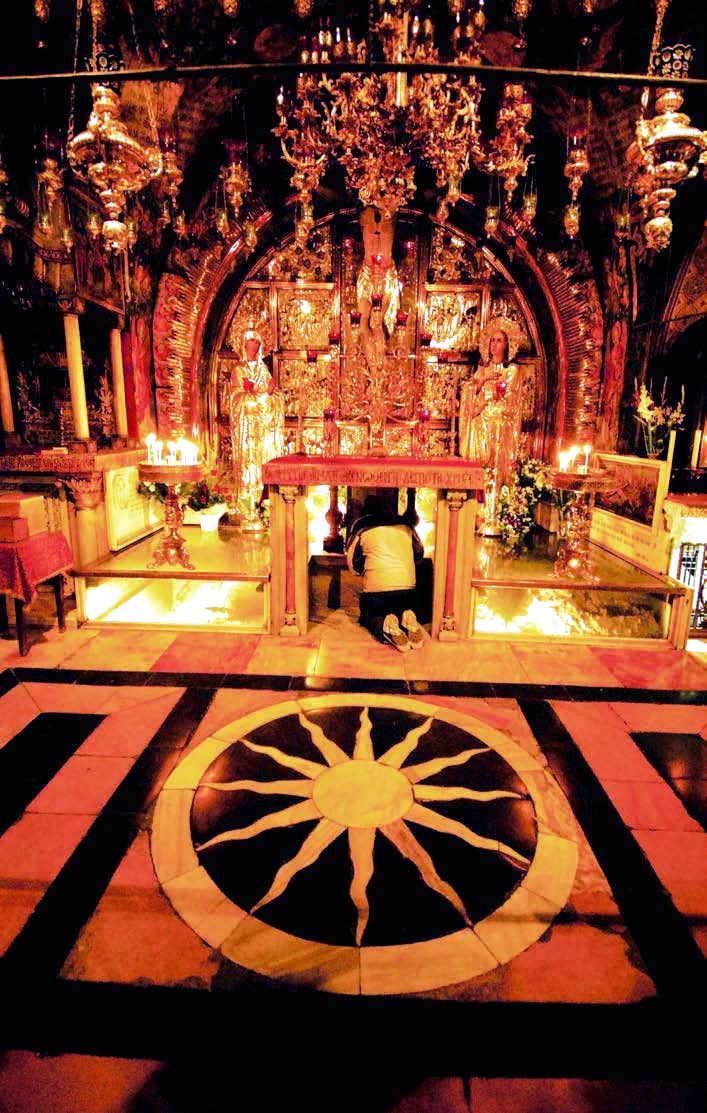

What should also be given some attention is the Coptic Chapel that is attached to the wall on the west side. A small amount of the stone of the Tomb can be seen below the little altar. I have been in this chapel several times. I found it to be very peaceful and spiritual.

- The Fire of 1808

In 1808 the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was extensively damaged by fire. The roof of the rotunda collapsed on to the edicule, destroying the cupola and much of the marble and limestone cladding but leaving the interior relatively undamaged. The door of the edicule survived the fire and is preserved today in the Museum of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate. Blackened and slightly charred near the bottom on the outside but otherwise intact, the door seems to have protected the interior from the worst effects of the heat and smoke, although half the hangings in the Chapel of the Angel were scorched.

The Earthquake of 1927

The earthquake of 1927 threatened the whole structure with collapse, but it was not until March 1947 that it was strapped together by a cradle of steel girders put in position by the Public Works Department of the British Mandatory Government of Palestine, the last of their works in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Since then nothing has been done. The present state of the unsupported east and west walls is perilous, elements in the east front having moved as much as 3 cm in the years 1990-1993.

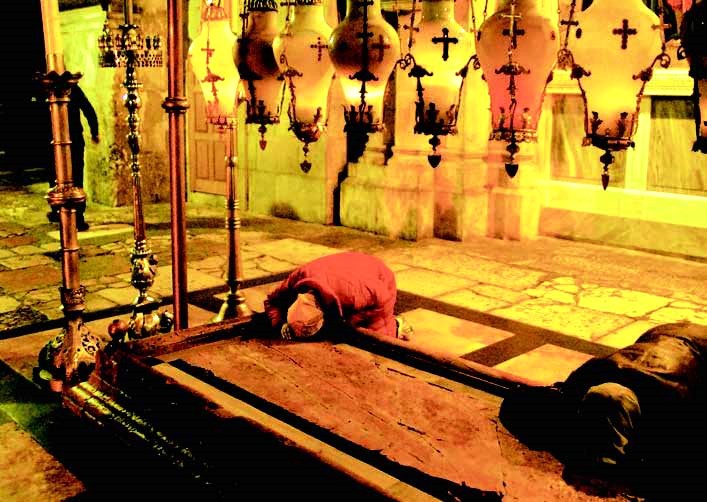

The Interior of the Tomb

Inside the tomb there is the actual burial couch which is usually covered with richly embroidered cloths, and the ledges around the couch are adorned with many candles. The religious communities have their own section of the burial chamber as well as their own section of the Church itself.

The Tomb of Christ?

Well, after this brief and inadequate survey of chroniclers, eyewitness accounts, and archaeological investigations, we still come back to the basic question: "Is it the tomb of Christ?"

Martin Biddle quotes the former City Archaeologist of Jerusalem, Dan Bahat as follows:

"We may not be absolutely certain that the site of the Holy Sepulcher Church is the site of Jesus' burial, but we certainly have no other site that can lay a claim nearly as weighty, and we really have no reason to reject the authenticity of the site."

The next question to ask is: Did the edicule survive the ravages of war during the following centuries?

I quote a paragraph of Biddle as it reports succinctly what happened during the succeeding centuries. He writes:

"The churches of Jerusalem were untouched by the Arab conquest of the city early in 638 but were not so fortunate in 1009. In that year, the Fatimid Caliph of Egypt, al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, (996-1021) ordered Yaruk, governor of Ramla, 'to demolish the Church of the Resurrection, to remove its (Christian) symbols, and to get rid of all traces and remembrance of it.' Yaruk's son and two associates 'seized all the furnishings that were there and knocked the church down to its foundations, except for what was impossible to destroy and difficult to grub up to take away.' Al-Husayn ibn Zahir al-Wazzan 'worked hard to destroy the tomb and to remove every trace of it and did in actual fact hew and root up the greater part of it.'"

This is just one example of the ravages that took place at this site. The fact that we have any of it left today is no less than a miracle!

And what of Constantine's church that was built over the edicule? This is what Biddle reports as follows:

"Constantine's church of the Martyrion was almost totally destroyed, never to be rebuilt, but even of this church the eastern wall and doorways still stand in part to a height of 4.6 meters. The outer wall of the Rotunda of the Anastasia survived to over twice this height, 'almost right round the whole edifice,' 'all round the rotunda,' to the underside of the internal and external cornices. The roof and the interior of the rotunda with its columns and piers were brought down, the rubble itself probably encumbering and thus protecting the lower parts of the outer walls. These were thus, it seems, impossible to destroy.' To some extent, this rubble may also have protected the lower parts of the edicule and rock-cut tomb within. Here, ibn Zahir destroyed 'the greater part,' leaving the implication that he did not destroy all, whether of the rock or of Constantine's enclosing edicule. As a comparison of the descriptions made before and after 1009 shows the rock-cut roof and much, perhaps all, of the west and east walls were removed, but the south wall and the burial couch survived and possibly part of the north wall in so far as this did not form part of the north side of the burial couch itself. The way in which the western half of the medieval edicule reflected what we now believe to be the form of Constantine's edicule also suggests that there was something left from which to start again. Only detailed investigation and records made when restoration is undertaken will perhaps show just how much did survive al-Hakim's attack."

The Tomb and Edicule Their Future

We have read and heard of the many disagreements between the Church communities that have responsibilities for sections of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher as well as the edicule. Whatever may have been the situation in the past, the present is much more harmonious. I quote from the final paragraph of the author's preface:

"One sometimes reads in the press about the problems which divide the religious communities in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. What has happened to the actual building in recent years shows that the reality is somewhat different. In the 1960s and 1970s, the church was brilliantly restored by a Common Technical Bureau working for the three great communities. The columns, walls, and dome of the rotunda surrounding the edicule were all restored as a part of this program. In 1996 the decoration of the dome was completed, the scaffold removed, and on 2 January 1997, the works were dedicated in a ceremony intended to mark the beginning of a triennium of preparation for the Great Jubilee of AD 2000. Plans were being made to restore the floor of the rotunda, hopefully before the Millennium, but It didn't happen. In due course, the decisions will be taken which will lead to the restoration of the edicule. This extensive and successful program, now well on its way to completion, is not a catalogue of dissent and delay but a record of agreement and achievement." (p. xii)

The edicule is in a bad state of repair. The earthquake of 1927 damaged the Church and also the edicule. The Church dome was beautifully restored by 1935, but the edicule was not attended to.

In the improved ecumenism of the 1960s, restoration became possible. The three religious communities - Greek Orthodox, Latin, and Armenian agreed on the restoration. On the 2nd of January 1997, the restored dome was at last inaugurated in an ecumenical celebration, but again, the edicule remained in a bad state.

The outward appearance of the present edicule dates only from 1809-10. It was badly shaken in the earthquake of 1927 as previously mentioned. It had to be strapped together, and those pieces of steel are still there. I saw them in 1997 and 2007. In fact, it is in such a bad state that experts believe it should be dismantled, stone by stone, down to the floor. This would also enable some archaeological study to be made.

A Personal Postscript

I have had the privilege of visiting the Holy Land in 1997 and 2007. The first occasion was with my wife, Libby, and we stayed in the Old City at a hostel for the Easter celebrations. To say that it was inspiring would be an understatement. The second occasion was in 2007 when my daughter, Janet, and I travelled to Israel in the summer and spent two weeks on an archaeological dig on the shores of the Sea of Galilee. Again, we visited Jerusalem, but this time it was mainly for archaeological purposes.

As a result of these two visits I have had the privilege of visiting a number of places sacred to the Christian religion. The tomb of Christ was one of them. I can vouch for the descriptions I have quoted in this paper regarding the present state of repair of the tomb and edicule. I am amazed that nothing has been done for so long. However, there appear to be signs that the three religious communities are planning major restorations of the floor of the Church itself, and I am optimistic that this will lead them inevitably to a renovation or rebuilding of the edicule that houses the place in which our Lord was laid.

- Acknowledgement

Finally, I wish to once again make acknowledgement of the reference that I have used for this presentation. The author is Martin Biddle, Professor of Medieval Archaeology and Astor Senior research Fellow in Medieval Archaeology at Hertford College, Oxford. The title of his book is The Tomb of Christ published in 2000 by Sutton Publishing. (ISBN 0 7509 2525).

Sir Knight Fred Shade is a member of the order in Victoria, Australia. He has been Chaplain of his Preceptory (Metropolitan No. 2) for many years and holds the rank of Past Great 2nd Constable. He was the founding Secretary of the Victorian Knight Templar Study Circle and its second president. He can be contacted on email: fredshade@westnet.com.au